Medieval clothing and textiles

Byzantium

The Byzantines made and exported very richly patterned cloth, woven and embroidered for the upper classes, and resist-dyed and printed for the lower. By Justinian's time the Roman toga had been replaced by the tunica, or long chiton, for both sexes, over which the upper classes wore various other garments, like a dalmatica (dalmatic), a heavier and shorter type of tunica; short and long cloaks were fastened on the right shoulder.

Leggings and hose were often worn, but are not prominent in depictions of the wealthy; they were associated with barbarians, whether European or Persian.

Early medieval Europe

The elite imported silk cloth from the Byzantine, and later Muslim worlds, and also probably cotton. They also could afford bleached linen and dyed and simply patterned wool woven in Europe itself. But embroidered decoration was probably very widespread, though not usually detectable in art. Lower classes wore local or homespun wool, often undyed, trimmed with bands of decoration, variously embroidery, tablet-woven bands, or colorful borders woven into the fabric in the loom.

High middle ages and the rise of fashion

Clothing in 12th and 13th century Europe remained very simple for both men and women, and quite uniform across the subcontinent. The traditional combination of short tunic with hose for working-class men and long tunic with overgown for women and upper class men remained the norm. Most clothing, especially outside the wealthier classes, remained little changed from three or four centuries earlier.

The 13th century saw great progress in the dyeing and working of wool, which was by far the most important material for outer wear. Linen was increasingly used for clothing that was directly in contact with the skin. Unlike wool, linen could be laundered and bleached in the sun. Cotton, imported raw from Egypt and elsewhere, was used for padding and quilting, and cloths such as buckram and fustian.

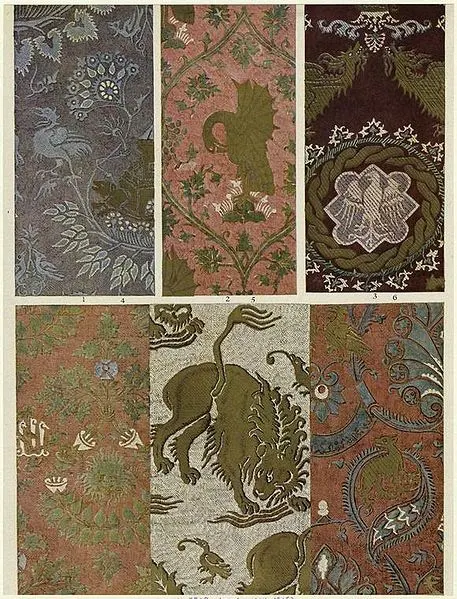

Crusaders returning from the Levant brought knowledge of its fine textiles, including light silks, to Western Europe. In Northern Europe, silk was an imported and very expensive luxury. The well-off could afford woven brocades from Italy or even further afield. Fashionable Italian silks of this period featured repeating patterns of roundels and animals, deriving from Ottoman silk-weaving centres in Bursa, and ultimately from Yuan Dynasty China via the Silk Road.

Cultural and costume historians agree that the mid-14th century marks the emergence of recognizable "fashion" in Europe. From this century onwards Western fashion changes at a pace quite unknown to other civilizations, whether ancient or contemporary. In most other cultures only major political changes, such as the Muslim conquest of India, produced radical changes in clothing, and in China, Japan, and the Ottoman Empire fashion changed only slightly over periods of several centuries.

In this period the draped garments and straight seams of previous centuries were replaced by curved seams and the beginnings of tailoring, which allowed clothing to more closely fit the human form, as did the use of lacing and buttons. A fashion for mi-parti or parti-coloured garments made of two contrasting fabrics, one on each side, arose for men in mid-century and was especially popular at the English court. Sometimes just the hose would be different colours on each leg.

Renaissance and early modern period:

Renaissance Europe

Silk-weaving was well established around the Mediterranean by the beginning of the 15th century, and figured silks, often silk velvets with silver-gilt wefts, are increasingly seen in Italian dress and in the dress of the wealthy throughout Europe. Stately floral designs featuring a pomegranate or artichoke motif had reached Europe from China in the previous century and became a dominant design in the Ottoman silk-producing cities of Istanbul and Bursa, and spread to silk weavers in Florence, Genoa, Venice, Valencia and Seville in this period.

As prosperity grew in the 15th century, the urban middle classes, including skilled workers, began to wear more complex clothes that followed, at a distance, the fashions set by the elites. National variations in clothing increased over the century.

%20in%20the%20Garment%20Industry.jpg)

0 Comments